During a physical exam, your healthcare provider may perform a chest examination. It is sometimes referred to as a lung exam. This is especially important when trying to diagnose a respiratory condition. Though not all four parts are always utilized in every exam, this will depend on whether it is a yearly physical or a follow-up visit for a specific respiratory issue, these four simple steps, along with a detailed history, can be the key to a correct diagnosis. While more elaborate and complex technology exists, a thorough chest exam can make all the difference.

1. Inspection

The entire time your healthcare provider is treating you, they should be actively observing. They will try to determine your general comfort of breathing and whether there are any irregularities. The use of accessory muscles can indicate difficulty breathing, as could unusual breathing patterns and even the position of your body.

Patients with extreme pulmonary dysfunction will often sit upright. In distress, they may assume the tripod position, leaning forward and resting their hands on their knees. Your provider may look for physical abnormalities that signal an issue. Pectus excavatum, or concave chest, is the most common. Pectus carinatum or “pigeon breast” which occurs when the breastbone and ribs are pushed outward is another. Barrell chest, when the chest becomes overly expanded, may suggest COPD, asthma or cystic fibrosis. Tracheal deviation, when the trachea is not midline, is another abnormality to note.

Your healthcare provider will observe your pattern of breathing. If you become short of breath while speaking it may indicate a pulmonary function problem. Specifically breathing through pursed lips often is associated with emphysema. Your healthcare provider will also look for any audible noises during breathing such as wheezing or gurgling. If someone is breathing normally, they will likely take 10-14 breaths per minute, and have a 1:3 ratio for inspiration vs expiration. Three abnormal breathing patterns are:

- Cheyne-Stokes breathing: Characterized by periods of apnea, or breathlessness, that are spread between cycles of increasing then decreasing respiratory rates.

- Kussmaul breathing: Rapid, large-volume breathing that can indicate metabolic acidosis.

- Biot breathing: A pattern that alternates between abnormally rapid breathing, abnormally slow breathing and apnea, which could indicate respiratory failure.

2. Palpation

The second part of a chest exam requires your healthcare provider to feel areas of your chest to determine if there is tenderness, a mass, asymmetry, unusual movement of the diaphragm during breathing (called diaphragmatic excursion), or crackling or creaky joints (called crepitus).

You may also be asked to repeat a specific phrase, like “one, two, three,” while your provider keeps their hands on your chest to see if the vibrations can be felt through the body (called vocal fremitus). Areas of increased vibration correspond to areas of increased tissue density, which could signal a problem area. Too little vibration may indicate air or fluid in the pleural spaces or a decrease in lung tissue density, which may indicate COPD or asthma.

3. Percussion

The third component of the chest exam is percussion a more advanced method of determining the density of the tissue in your chest. Your healthcare provider will lay one hand on your chest while using the other to tap different spots on your chest. Sections of a healthy lung will resonate, sounding clear. Denser tissue, or areas where there is an abnormal collection of fluid, will sound duller to percussion. If your healthcare provider finds an abnormality, they may use percussion around the area of interest to understand the extent of the problem more clearly.

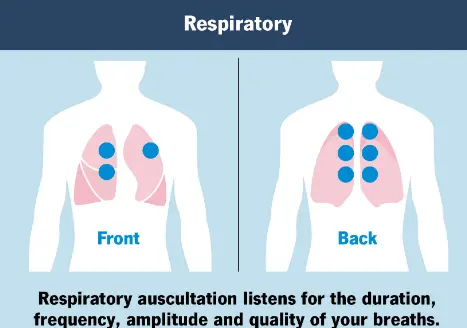

4. Auscultation

During this step, your healthcare provider will use a stethoscope to listen to the sound of your heart, lungs and belly. You will be asked to sit upright and take deep breaths while they place a stethoscope on your chest, back and abdomen, assessing all zones of the lungs. Though it’s one of the oldest techniques, it is a quick way for your provider to confirm or rule out many medical conditions.

For your lungs specifically, your healthcare provider will listen for:

- Duration: measuring the length of your inhales and exhales

- Frequency: measuring how often they feel sound waves or vibrations and it they have a usual pitch

- Amplitude: measuring how loud and intense your breathing is

- Quality: listening for any abnormal or distinctive sounds: such as wheezing, crackling, squawking, absent or high-pitch sounds.

There are three types of normal breath sounds your provider will listen for: tracheal, bronchial and vesicular. Adventitious sounds are heard in addition to the expected normal breath sounds. Specifically, warning signs and various abnormal sounds include:

- Absence: When no airflow is heard in the region being auscultated, this can signal a pneumothorax, hemothorax or pleural effusion.

- Crackles: Generated by small airways snapping open on inspiration, the popping sound can be course or fine depending on the size of the airway. It may be a sign of COPD, pneumonia or heart failure.

- Pleural rub: A loud sound like sandpaper is a sign that your lungs or the tissue around them are irritated. This can be a sign of pleurisy, pneumothorax or pleural effusion.

- Rhonchi: Course, loud sounds like snoring, signal a blockage in your larger airways. This can be caused by pneumonia, COPD or cystic fibrosis.

- Stridor: A loud and high-pitched sound that occurs when there is a blockage in your upper respiratory tract. It can be caused by epiglottitis, anaphylaxis or vocal cord dysfunction.

- Wheezes: Sounding like a high-pitched hissing, wheezes can mean that mucus is preventing your lungs from filling completely or that an airway has collapsed. This can be caused by COPD, asthma or pulmonary edema.

Depending on what your provider hears during your chest exam, as well as your other symptoms, additional lung tests or procedures may be recommended. Learn more about these tests, how your lungs work and how to improve your lung function.

Blog last updated: June 7, 2024